Overview

Since its release it has been played and recommended by several YouTubers and Steam curators and received very positive reviews.

Development

Programming

To handle enemy behaviours, I used a multi-layered state machine. This manifested as a framework were each enemy inherited from a base class which contained their current behaviour. This is an object which instructs the enemy on how to move, damage the player and when to switch behaviours using functions from the base class. it knows which of these options to perform because most of the enemy behaviours contain a sub-state. For example, a simple roaming behaviour might look like this:

public abstract class Enemy : MonoBehaviour

{

EnemyBehaviour currentBehaviour;

protected void SwitchToBehaviour(EnemyBehaviour newBehaviour)

{

if (currentBehaviour != null)

currentBehaviour.End();

currentBehaviour = newBehaviour;

currentBehaviour.Start();

}

protected virtual void Update()

{

if (currentBehaviour != null)

currentBehaviour.Update();

}

abstract class EnemyBehaviour

{

Enemy enemy;

public EnemyBehaviour(Enemy enemy)

{

this.enemy = enemy;

}

// Event Hooks

protected abstract void OnStart();

protected abstract void OnUpdate();

protected abstract void OnEnd();

protected abstract string GetDebugInfo();

}

}public class BasicEnemy : Enemy

{

const float roamingWaitTime = 4.0f;

void Start() => SwitchToBehaviour(new RoamingBehaviour());

class RoamingBehaviour : EnemyBehaviour

{

enum Substate

{

MovingToDestination,

Waiting

}

Substate substate;

float startedWaitTimestamp;

protected override void OnStart()

{

substate = Substate.MovingToDestination;

enemy.SetMoveDestination(GetRandomPointOnNavMesh());

}

protected override void OnUpdate()

{

switch (substate)

{

case Substate.MovingToDestination:

if (enemy.HasReachedMoveDestination())

{

startedWaitTimestamp = Time.time;

substate = Substate.Waiting;

}

break;

case Substate.Waiting:

if (Time.time >= startedWaitTimestamp + enemy.roamingWaitTime)

substate = Substate.MovingToDestination;

break;

}

}

}

}Most of the level behaviours are controlled by a system of triggers. At the beginning of each level, a trigger fires to check whether the challenge mode is enabled and, if it is, the environment is modified and the correct exit trigger is selected. I later reformed this idea into a single EventTrigger component which contains a list of conditions and outputs. These elements are user-defined by inheriting from the corresponding base class, at which point all children are found using reflection and made available to the GUI. Then they can be added to an EventTrigger in the scene.

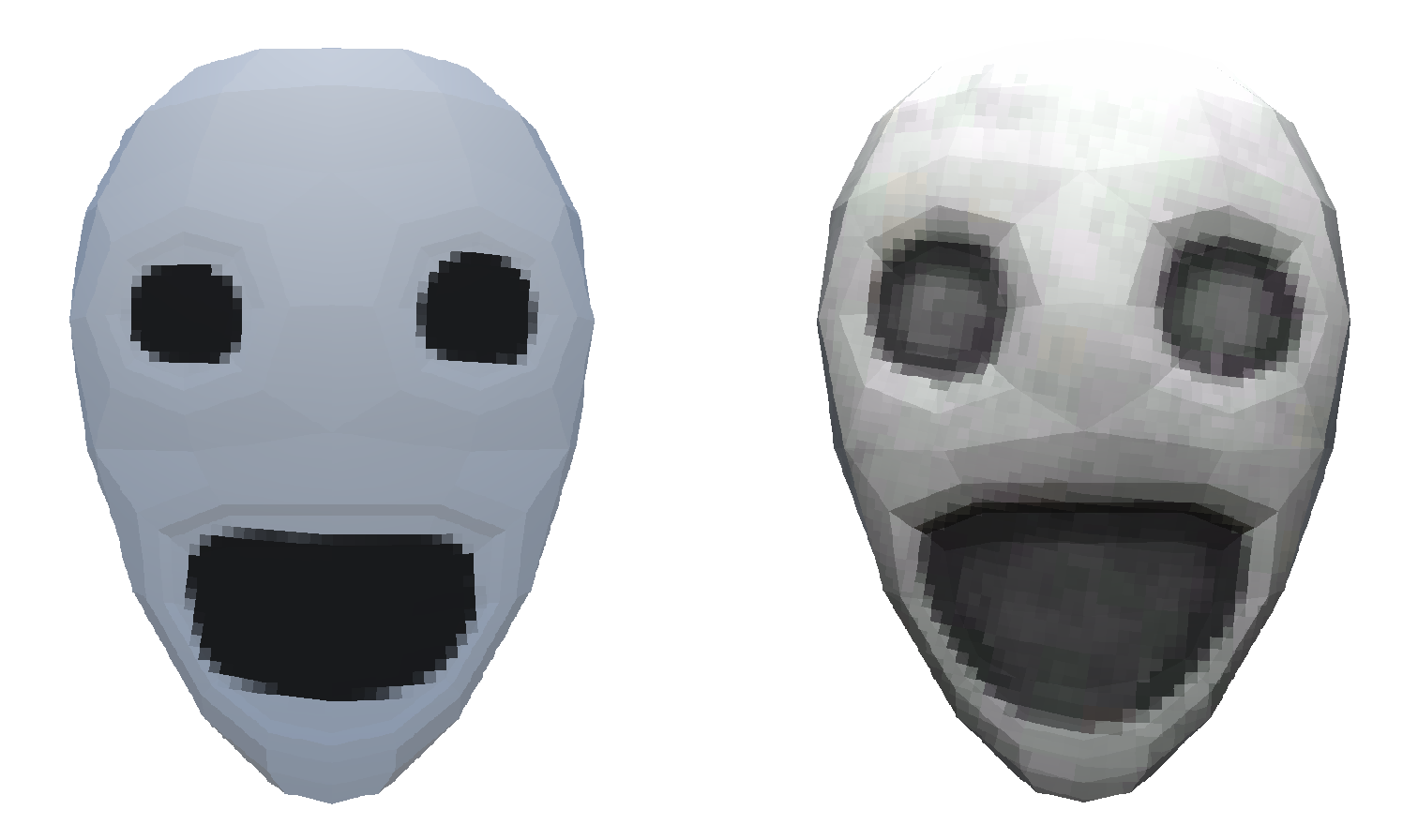

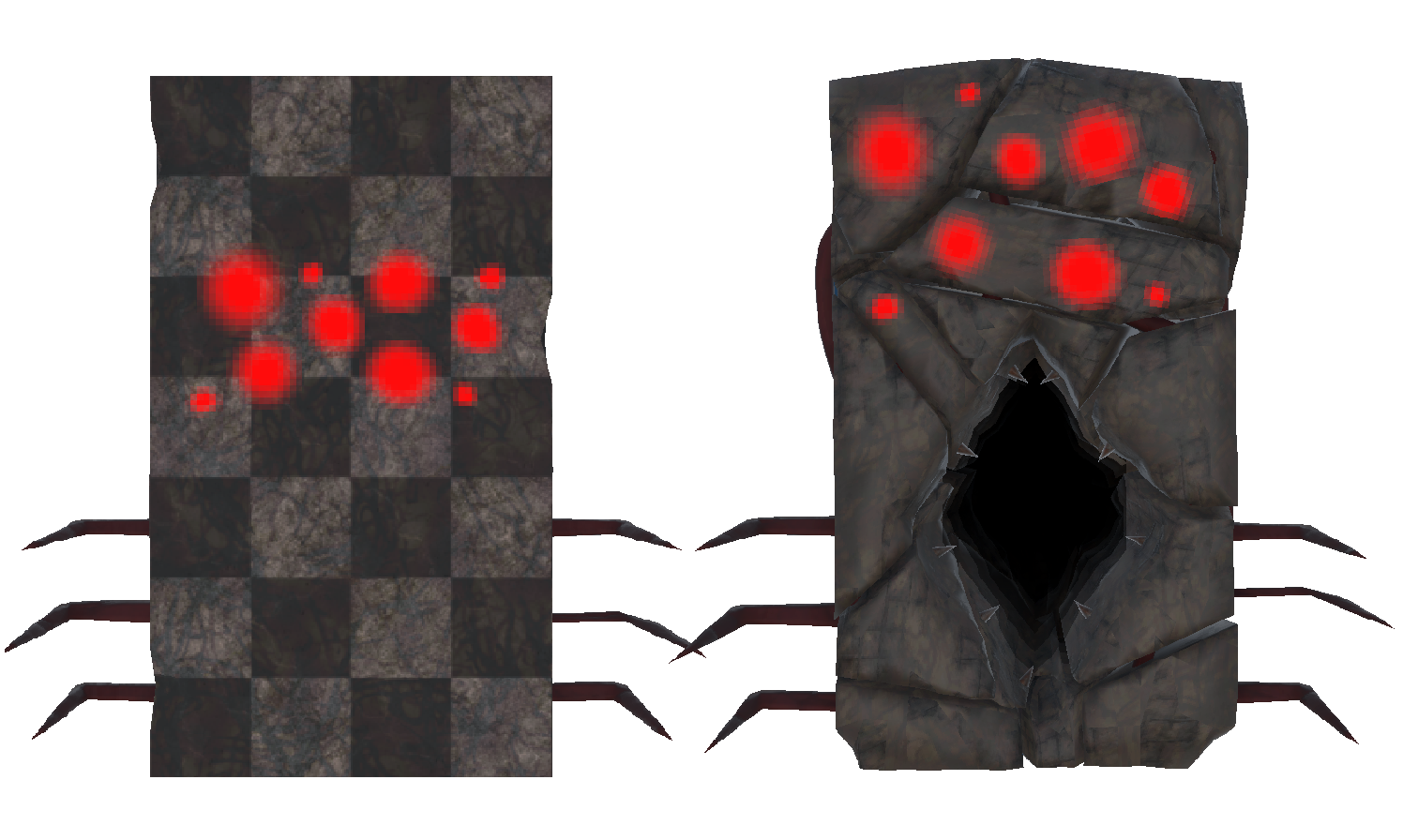

Modelling

Through making WtW, I was able to develop my 3D modelling skills and have since began using the low-poly / high-poly workflow in my newer models, and texturing them in Substance Painter. With these skills I released a post-launch update to polish many of the older models, though I still held to the game's their retro aesthetic.

Level Design

Equally tedious was level design. Every WtW level went through at least three complete do-overs, graphically and topographically. The size of the levels had to be just small enough for players to stumble upon their objectives, but just large enough to create dynamic encounters with the various monsters. A big problem the game faced during development was that players would get lost on the last power box, struggle for ages until their power went out and they had to start over. I combatted this with two changes:

- I introduced a proximity alert to the radar; which beeps faster the closer you are to an objective.

- I researched real-life interior design and implemented a hub-and-spokes system in each level.